Biological diversity of disease resistance to flower blight of Camellia japonica caused by Ciborinia camelliae in Goto, Japan

Chuji Hiruki

The Goto Camellia Society, Goto City, Nagasaki Prefecture, Japan

E-mail: chujihiruki@aol.com

Introduction

The Goto islands are located in the most westerly area of Japan and are surrounded by the ocean, which means that they are blessed with a very mild climate due to the warm Tsushima current. The whole area is covered with naturally grown yabu-tsubaki (Camellia japonica) and plantations are estimated to contain about 10 million camellia trees. For this reason the Goto islands have, for the first time, been designated a special economic district for the development of the camellia industry by the Japanese Government. Historically speaking, camellia trees in the Goto islands have been used as wind breaks to protect agricultural crops not only from violent storms in summer but also from cold northern winds in winter. At the same time camellia seeds have been an important source of high quality vegetable oil in the food industry. Furthermore, a new possibility has emerged in the cosmetic industry following the development of new technology by a major commercial company in Japan.

Thus, it is very important to maintain the constant supply of camellia oil for the sustained development of a new industry. The purpose of this research is to find possible reasons for the irregularity of seed production in yabu-tsubaki in the Goto Islands, which has been revealed by recent statistics, and to establish a technical basis to stabilize the production of camellia seed for the utilization of camellia oil.

Occurrence of flower blight in the Goto Islands and maintenance of street yabu-tsubaki

Flower blight on yabu-tsubaki in the Goto islands is believed to have been endemic for many years. However, accurate estimates of the damage caused are not available due to the lack of systematic disease surveys.

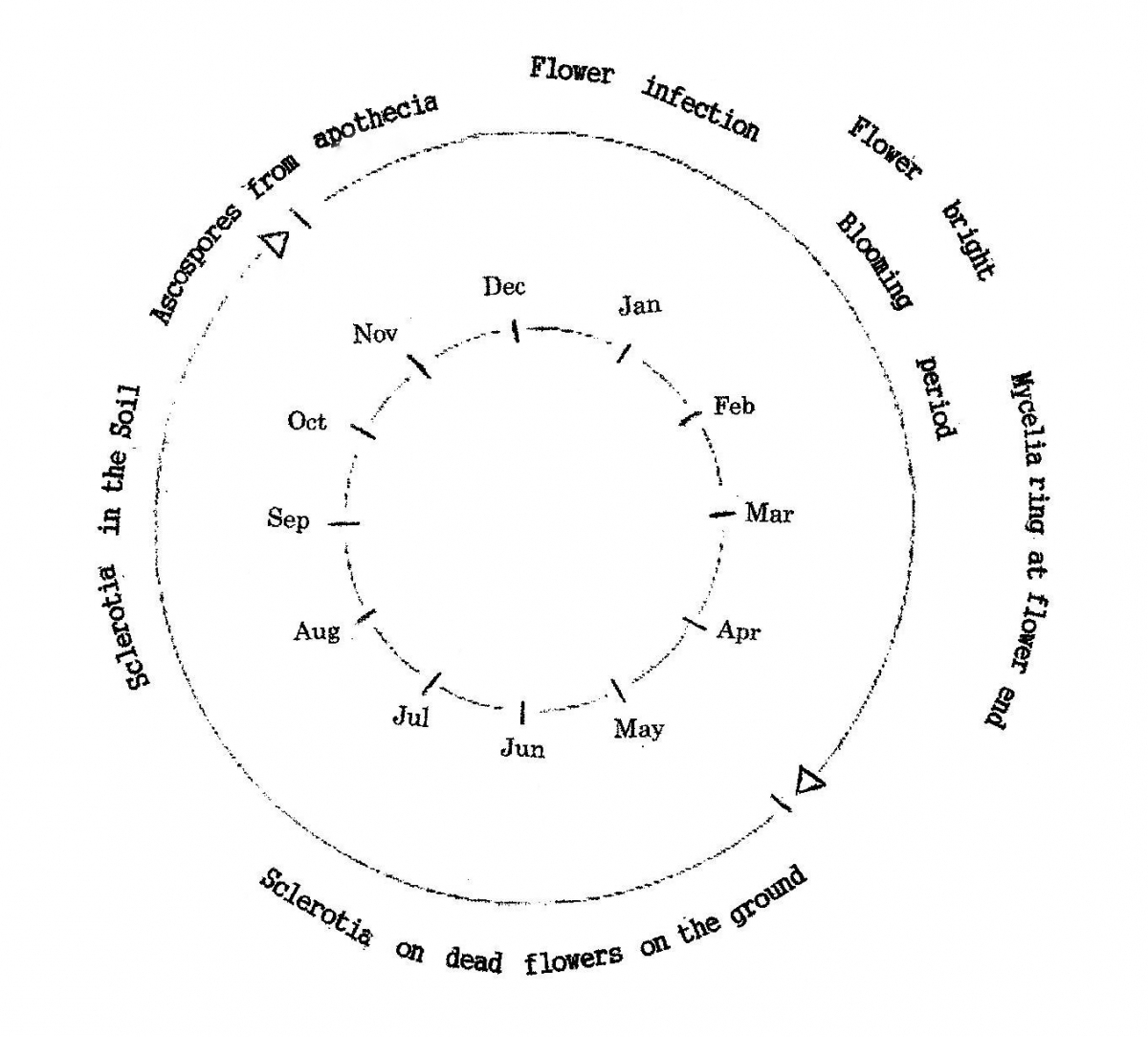

The fungal pathogen (Ciborinia camelliae) specifically infects the petal of camellia following the dissemination of ascospores from apothecia formed from the previous years' sclerotia in the soil. Normally prevailing infection in the field is known to occur from January to March. However, natural occurrence in the field has been observed in a certain area in the Goto islands as early as November. The life cycle of C. camelliae under natural field conditions of the Goto islands is shown in Figure 1.

Fig.1 The life cycle of Ciborinia camelliae in the Goto islands.

Yabu-tsubaki has been used as a symbol of Goto City for many years and more than 400 yabu-tsubaki are planted in both sides of city boulevards (Figure 2).

Fig. 2 A street scene of Goto City with Fig. 3 Deep watering through pipes

camellias as street trees. for healthy camellia growth.

The trees are regularly pruned and therefore the average number of floral buds per tree is limited to a range of 300-400, though potentially at least 1,000 floral buds could be produced.

Recently a new method has been introduced for water supply to maintain the healthy growth of street camellia trees (Figure 3). This improvement has resulted in the increased production of flowers by providing deep watering around root system of the street camellia trees in the boulevards, which was not available in the past (Figure 10). It is important to point out that the increase in the occurrence of flower blight coincided with the increase of flowers in the absence of effective disease control measures in recent years.

Fruit productivity of the selections of productive yabu-tsubaki in the Goto islands

During the three-year period between 1981 and 1983, extensive surveys to find highly productive yabu-tsubaki trees were conducted throughout the entire Goto islands. The surveys resulted in the selection of the 50 best trees and they were planted in the Ondake Botanic Garden (now a part of the Goto Camellia Forest Park) as a gene bank for the future use (Figure 4).

Fig. 4 Camellias selection of the most productive for camellia oil being cultivated in the Goto Camellia Forest Park.

In 2012, ten yabu-tsubaki trees out of these selections were used for evaluating seed production under field conditions where all trees were exposed equally to natural infections by C. camelliae.

Abundant formation of apothecia and frequent release of the ascospores under the camellia trees in the experimental plots were confirmed (Figures 5 and 6). Flowers were examined for flower blight infection and the number of flowers was recorded for each tree.

Fig. 5 Abundant formation of apothecia Fig.6 A fallen yabu-tsubaki flower showing flower

Ciborinia camelliae blight infection and young apothecia of Cibornia

camelliae on the ground.

Table 1. The percentage of camellia fruits to flowers from the 1981-83 selections of yabu-tsubaki

| Tree | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Flower no.* | 258 | 185 | 94 | 172 | 78 | 65 | 127 | 87 | 106 | 118 |

| Fruit no.** | 31 | 68 | 58 | 34 | 20 | 30 | 42 | 34 | 52 | 13 |

| Percentage | 12 | 37 | 62 | 20 | 26 | 46 | 33 | 39 | 49 | 11 |

* Counting date: February 18, 2013

** Counting date: August 16, 2013

Fruit productivity of street yabu-tsubaki from different areas in Goto City

In 2012, ten street trees were selected from each of five different areas (A-E) in Goto City and the evaluation of fruit production was carried out. The results obtained from different areas showed different degrees of disease resistance. The most obvious result was that ' Tama-no-ura' was highly susceptible to flower blight (Figure 7) and produced least fruits among camellia trees from the five areas tested (Table 2), although all 'Tama-no-ura' produced their attractive flowers profusely as the result of the recent improvement in the supply of water for the street camellia trees (Figure 8).

Table 2. The percentage of camellia fruits to flowers from 'Tama-no-ura' (Camellia japonica) in Area A.

| Tree | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Flower no.* | 250 | 182 | 305 | 380 | 458 | 328 | 302 | 282 | 350 | 482 |

| Fruit no.** | 18 | 4 | 9 | 11 | 72 | 1 | 16 | 0 | 18 | 54 |

| Percentage | 7 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 16 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 11 |

* Counting date: February 19, 2013

** Counting date: August 17, 2013

Fig.7 Flower blight of 'Tama-no-ura' Fig.8 Abundant flowering of 'Tama-no-ura’

Fig.7 Flower blight of 'Tama-no-ura' Fig.8 Abundant flowering of 'Tama-no-ura’

as the result of watering improvement.

Yabu-tsubaki from Area B contained one plant that produced fruits from over 50 percent of flowers. However, the other trees from the remaining areas produced fruits less than 50 percent with different degrees of disease resistance.

Fig.9 Prevalent occurrence of flower blight Fig.10 The increased production of flowers

of yabu-tsubaki in the street in Goto City of yabu-tsubaki by providing deep watering

Disease resistance to flower blight in yabu-tsubaki in the Goto-islands

While the floral tissue of 'Tama-no-ura' follows the typical process of camellia flower blight from the initial development of black/brown petal lesions and blight to premature flower fall (Figures 7, 11 and 12), certain yabu-tsubaki trees produced normal fruits in spite of petal infection.

Fig.11 Initial stage of flower blight infection Fig.12 Rapid spread of petal infection

Fig.11 Initial stage of flower blight infection Fig.12 Rapid spread of petal infection

of 'Tama-no-ura'. of 'Tama-no-ura'.

It was observed in such plants that the enlargement of petal lesions formed after initial infection was limited to a small area and the pistil and ovule remained healthy. In contrast, susceptible yabu-tsubaki became infected rapidly and the final death of the ovary tissue occurred through its affected pistil.

Discussion

C. camelliae is the causal agent of the disease known as camellia flower blight which results in devastating damage not only in ornamental cultivars of camellia but also several species of Camellia including yabu-tsubaki (Hara,1919; Hansen & Thomas, 1940; Taylor & Long, 1998; Taylor, 2004; Hiruki, 2014). Most commercial cultivars are highly susceptible. Some disease resistance in certain commercial cultivars and species of Camellia has been reported (Taylor, 2004; Vingnanasingam et al. 2001; Denton-Giles et al., 2013). However, the concrete basis of disease resistance is yet to be established.

All yabu-tsubaki selections that have been preserved in the Ondake Botanic Garden are from field originated heterogeneous seeds. Therefore, it is not surprising to find a selection resistant to flower blight among them. Likewise, street yabu-tsubaki in Goto City is also grown originally from seeds of different origins. The fact that these yabu-tsubaki trees are genetically heterogeneous means that it may be possible to find a yabu-tsubaki tree that is a possible carrier of gene(s) resistant to flower blight as the result of natural selection under the continued exposure to infection by C. camelliae.

Apparent disease resistance to camellia flower blight appears to be based on the fact that in the flowers from an apparently resistant yabu-tsubaki tree, solid local lesions are formed after initial infection and the spread of the diseased area is limited due to the necrotic tissues. Thus, the infected flowers are only partially affected, keeping the pistil and ovule relatively intact and free from destructive invasion by the fungus. Therefore, in spite of infection by C. camelliae, the formation of fruits can continued normally.

The creation of resistant interspecific hybrids between the Camellia species of Theopsis section (Sealy, 1958) and susceptible Camellia section has been accomplished previously (Ackerman, 1973). It has been shown recently that species of Theopsis have the highest level of incompatibility, which makes them the preferable candidates for future resistance breeding strategies in camellia flower blight research (Denton-Giles et al., 2013).

In the future, such interspecific breeding programs should be established for the development of resistant cultivars of yabu-tsubaki for the production of seeds for camellia oil industry.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the members of the Goto Camellia Society, Mrs J. Iseki, Mrs M. Katayama, Mr and Mrs Kimura, Mr K. Matsushima, in particular, for their technical assistance in a part of this project.

References

Ackerman, W. L. 1973. Species compatibility relationships within the genus Camellia. Journal of Heredity 64:356-358.

Denton-Giles M., R. E. Bradshaw, P. P. Dijkwel, 2013. Ciborinia camelliae (Sclerotineace)induces variable plant resistance responses in selected species of Camellia. Phytopathology 103:725-732.

Hansen, H. H. and H. E. Thomas, 1940. Flower blight of Camellias. Phytopathology 30:166-170.

Hara, K. 1919. On a Sclerotinia disease of camellia. Dainippon Sanrinkwaiho 436:29-31.

Hiruki, C. 2014 . Current status of research on flower blight. Tsubaki 53:(In press).

Sealy, J. R. 1958. A revision of the genus Camellia. The Royal Horticultural Society, London.

Taylor, C. and P. Long. 1998. Camellia flower blight in New Zealand.Proc. 51st N.Z. Plant Protection Conf. 1998:134-137.

Taylor, C. H. 2004. Studies of camellia flower bright (Ciborinia camelliae Kohn), PhD Thesis. Massay University, Palmerston North, New Zealand.

Vingnanasingam, V., P. G. Long, R. E. Rowland. 2001. Mechanisms of resistance to Ciborinia camelliae in Camellia spp. New Zealand Plant Protection 54: 248.

Web design by Tribal Systems